Table of Contents

A privacy enhancing technology is any technical method that protects the privacy or confidentiality of sensitive information. This broad definition covers a range of technologies, from relatively simple ad-blocking browser extensions to the Tor network for anonymous communication. We are interested in a narrower set of technologies, that we divide into two categories: traditional and emerging PETs.

Traditional PETs are well-established privacy techniques, such as encryption schemes that secure information in transit and at rest, and de-identification techniques such as tokenization and k-anonymity.

Emerging PETs are a group of technologies that have begun to provide novel solutions to privacy challenges in modern data-driven systems. There is no fixed definition of what PETs fall into this group, but here we primarily consider five technologies: homomorphic encryption, trusted execution environments, secure multi-party computation, differential privacy, and systems for federated data processing.

Examples of traditional PETs

Encryption is one of the principal security technologies used to protect information. Encryption converts legible data into a so-called ciphertext - a representation of the data that is unreadable by a human or a computer. The data can only be read by first decrypting it, which requires access to an appropriate decryption key. Thus, data is kept secret from everyone who does not have access to this key.

In transit encryption secures data as it flows between two connected computers. For example, when you login to a website your username and password are first encrypted before being sent over the internet to the website in question, ensuring that a bad actor eavesdropping on your connection is not able to learn your credentials.

At rest encryption secures data for storage on disk. For example, you may well be using a computer that stores data on an encrypted hard drive. This ensures that data stored on your computer cannot be read by an unauthorised user attempting to access your computer.

In transit and at rest encryption are mature technologies that are commonplace. They should be considered standard practice when sending information over the internet, and when storing sensitive information on disk.

We define a de-identification technique as any data transformation or modification that reduces the amount of information about an individual or entity in a dataset, and/or reduces the risk that an individual or entity can be re-identified. These methods are distinguished from the PETs described above in that they involve direct manipulation of the raw data, rather than being mechanisms for protecting confidentiality whilst maintaining maximum utility over the underlying data.

Some examples of de-identification techniques are:

- Redaction: deleting an entire record or field, or obfuscating part of a record or field (e.g. deleting all but the last 4 digits of a credit card number)

- Tokenization: replacing a real value with a randomly generated value

- Hashing: applying a function to a value to produce a fixed-length value (or hash)

- Generalization: transforming a value to a less precise or bucketed value, e.g. replacing a height of 179cm with a range 170-180cm

- k-anonymity: applying a combination of de-identification techniques so that any record in the dataset becomes indistinguishable from (k-1) records

Limitations to consider

- No matter what level of de-identification techniques are applied to personal data, there is always a residual risk that data can be re-identified by linking it with other datasets, inferring information from proxy variables, or by applying advanced data mining techniques

Examples of emerging PETs

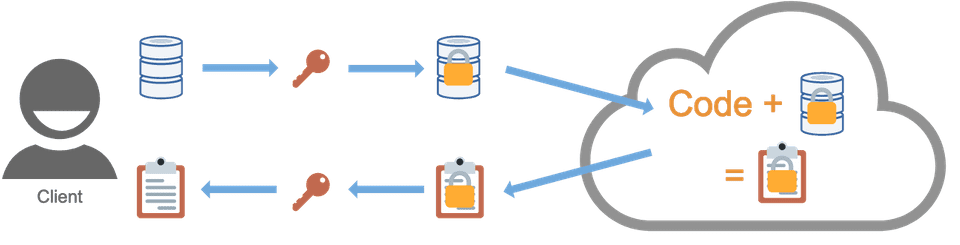

Homomorphic encryption enables computation directly on encrypted data. Whereas traditional encryption schemes facilitate the encryption of data in transit and at rest, homomorphic encryption schemes additionally facilitate encryption in process.

Homomorphic encryption can enable data processing to be outsourced to an untrusted third party. A data controller homomorphically encrypts their data, sends it to a third party data processor, the processor computes directly on the encrypted data producing an encrypted result, and the result is sent to the controller, who decrypts it. In this way, processing of sensitive data can be outsourced to third parties without having to establish trust, since the data remains encrypted throughout.

Similarly, homomorphic encryption may provide assurance to an organisation conducting their own data processing within a computing environment they do not fully trust, such as when using cloud infrastructure.

Homomorphic encryption schemes are separated into three categories, depending on the different types of operations that the scheme permits:

- Partial homomorphic encryption (PHE): permits only a single type of operation (e.g. addition) on encrypted data.

- Somewhat homomorphic encryption (SHE): permits some combinations of operations (e.g. some additions and multiplications) on encrypted data.

- Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE): permits arbitrary operations on encryption data.

Limitations to consider

- FHE allows arbitrary operations, but existing schemes are generally impractical as they incur a significant computational overhead. However, this is an active area of research where improvements are likely to occur in the future.

- Whilst PHE and SHE schemes are more performant, they support only a limited number of operations, and the nature of the operations that will be required by a system must be known in advance so that an appropriate specific encryption scheme can be selected.

- When outsourcing to a third party data processor, you should be mindful of the fact that because the third party cannot read any of the data, it may be more complicated to identify sources of error or develop new code against the data. You must therefore agree and adhere to a schema for the data in advance. Additionally, you may wish to share a plaintext dummy dataset that matches the schema of the real dataset, which the third party can use to develop and test their code against.

A trusted execution environment (TEE) is a processing environment isolated from a computer’s main processor and memory. Code or data held within this environment cannot be accessed from the main processor, and communications between the main processor and the TEE are encrypted.

The use cases for TEEs are similar to those for homomorphic encryption. A data controller can store their data within a TEE, to be operated on by an untrusted third party’s code also held within the TEE. Processing within the TEE occurs directly on unencrypted data - this means processing is likely to be faster than with homomorphic encryption, due to computational overhead incurred by the latter. Once calculated, the result is encrypted before being communicated back to the data controller, who has access to the appropriate decryption key.

Limitations to consider

- Use of TEEs still relies on a level of trust between parties that environments have been set up correctly, and as with any system there is always a level of security risk, e.g. via side-channel attacks, where information about the computation taking place within a TEE are inferred from signals produced by the computing system, such as power consumption or memory utilisation.

- As TEEs are hardware-based, they can be difficult to patch for vulnerabilities. For example, if a new side-channel attack vector is discovered, the physical chip containing the TEE may need to be replaced to mitigate the threat.

- There is no industry standard for interacting with TEEs, and each vendor's TEE design is bespoke. Applications leveraging TEEs thus must be coded according to the TEE vendor's API, which can lead to vendor lock-in.

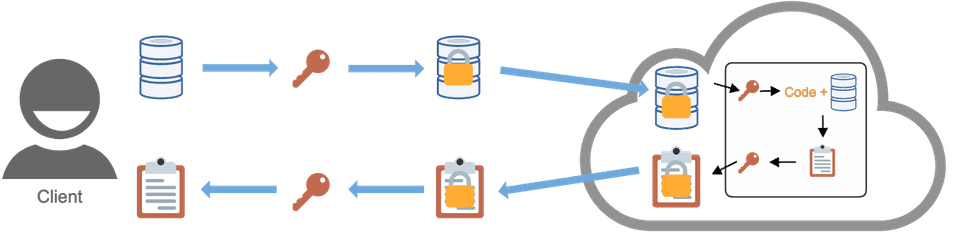

A multi-party computation (MPC) protocol enables a function taking input from multiple parties to be jointly computed, whilst each participating party keeps their input secret from the others. This typically involves fragmenting data over multiple networked nodes, such that each node hosts an “unintelligible shard” of data; inspection of a single shard does not reveal information about the original data. Each node computes a function on its shard, and the outcomes are aggregated into a final result.

To gain an intuitive understanding of MPC, consider a group of employees who want to determine their average salary, without revealing their individual salaries to one another. The below figure illustrates how MPC can be implemented using additive secret sharing, relying on basic mathematical properties of addition to split the computation between the parties such that salaries remain confidential. A correct result is obtained by recombining the results of each party’s computations. In practice, MPC protocols are more complex than this naive example, so as to be secure and support a wide range of operations.

Limitations to consider

- MPC protocols typically do not scale to generic data analysis tasks, meaning protocols have to be tailored to the specific task at hand.

- The need for nodes to talk to one another incurs a communications overhead in comparison to computing on a single, centralised dataset. This means that more complex protocols, that require a greater number of exchanges of information between nodes, may be impractical in real-world setups (especially where the nodes cannot be co-located within a low latency network).

- Dishonest and/or colluding parties could potentially disrupt an MPC protocol or leak information from the system - protocols should be designed for resiliency to any such attack vectors.

- There may be situations where the output from an MPC protocol can be used to infer information about the input data. As an illustrative example, imagine a system that calculates the percentage of individuals testing positive for a disease. You also know which individuals are participating in the study. If the result is 60%, you cannot determine which specific individuals are positive. However, if the result is 100%, you know with certainty that every individual is positive - personal information has been leaked. It is therefore important to understand the knowledge each participant in the network has, and what the range of potential results is, so that steps can be taken to minimise the risk of unintended information leakage.

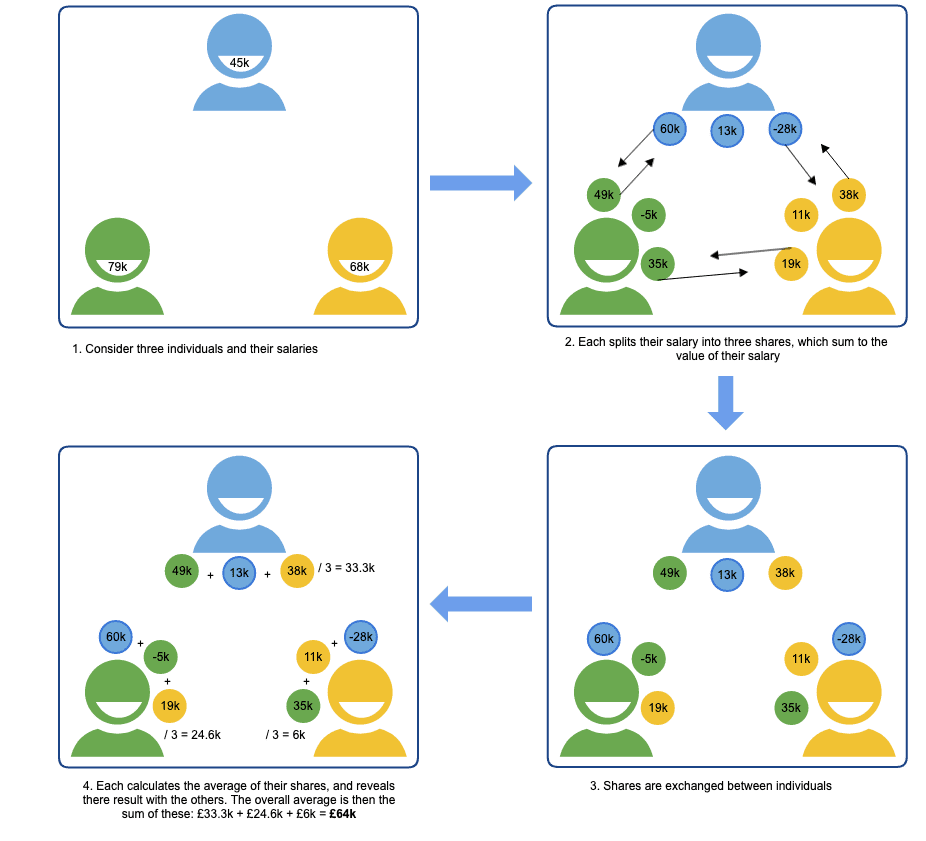

Differential privacy is a formal definition of privacy requiring that the output of any statistical analysis reveals no information specific to an individual in the dataset. An algorithm is typically made differentially private by adding noise to either the input data (local differential privacy) or to the output it produces (global differential privacy).

Differential privacy was developed in response to a 2003 paper by Irit Nisur and Kobbi Nissim which established the fundamental law of information recovery: overly accurate answers to too many queries of a statistical model enables dataset recovery. It follows that in order for the data used to build a model to be private, the model must necessarily be inaccurate to some extent. The amount of noise must be chosen carefully: too little and the dataset will not be private, too much and the output will be so inaccurate as to be useless. This is the privacy-utility trade-off.

The privacy-utility trade-off is formalised through the concept of Ɛ-differential privacy. Querying a model leaks information about the dataset, and the amount of information leakage increases with the number of queries. The parameter Ɛ quantifies this leakage and is known as the privacy budget. A user is stopped from performing further queries if they exceed their budget. Equivalently, Ɛ can be thought of as the maximum permissible difference between the result of a query performed against a model, and the result of an identical query performed against a model where an individual has been omitted from the dataset.

Limitations to consider

- Choosing a suitable valuable for the privacy budget is often challenging and highly context-specific

- Inaccuracies introduced by noise will be more pronounced for smaller sub-populations. For example, critics of the US Census Bureau's use of differential privacy have argued that it leads to an inaccurate understanding of local demographics, which could lead to communities being adversely affected by policy decisions that are made based on that data.

Federated analytics is a paradigm for executing a computer program against decentralised data. This involves a party uploading the program to the server or device on which the data is situated, executing it on the server or device with the data in situ, and communicating the results back to the originating party. In this way, no data is directly revealed to the party.

A subset of federated analytics is federated learning, which involves training a machine learning model on distributed datasets. The idea is to train local models directly on users' devices using local data, and then for the devices to share the weights of the resulting model with one another, in order for a new global model to be determined.

This can be centralized federated learning where a central server is responsible for coordinating the actions of participating devices (as shown below), or decentralized federated learning where the participating devices coordinate amongst themselves. In either case, the key feature is that user data never leaves the device, as only model weights are communicated.

An attacker could infer user information from these weights, and mechanisms (such as differential privacy, discussed below) are often incorporated to mitigate this.

Limitations to consider

- Although federated analytics provides no direct access to the data, it is possible that information about individuals in the dataset could be inferred from the output of the analysis. Performing the analysis in a differentially private way is one method for mitigating this risk.

- Not having direct access to the data can make it more difficult to develop, test, and troubleshoot code. Details of the schema and standards used by the remote database should be shared to help mitigate this, as well as dummy data that a developer can use to validate the functionality of their code.

- Training a machine learning model is computationally expensive, and is often accelerated using specialised hardware such as GPUs. In federated learning, you may not have control over the remote hardware that training will be performed on, which may limit the types of models you can build in this way.

All content is available under the Open Government License v3.0 except where otherwise stated.